Tales From The English River…

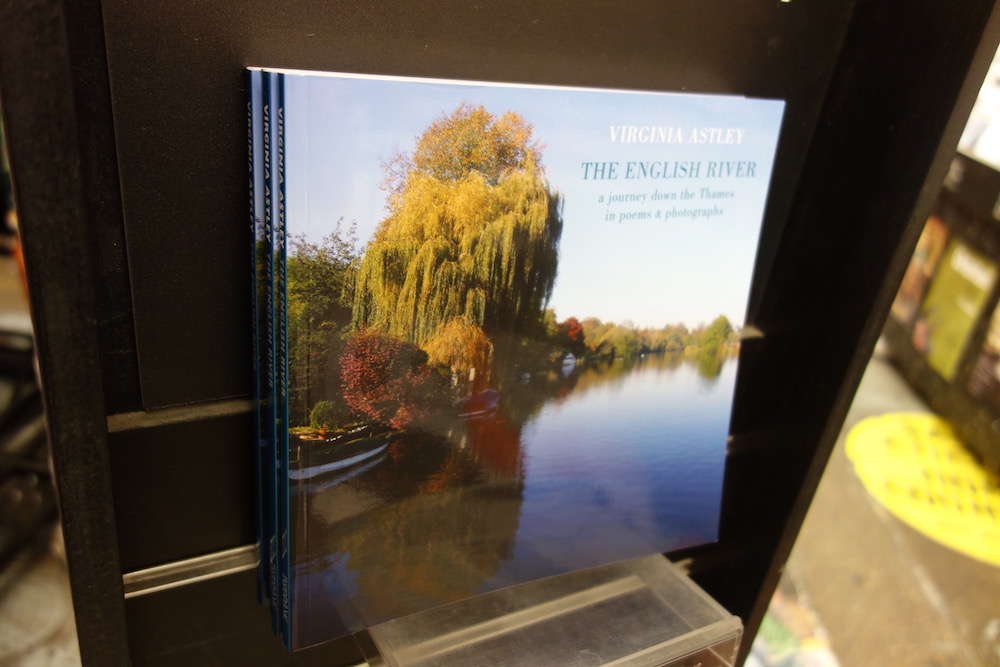

With the publication of The English River, Virginia Astley has reached a milestone in a writing career that’s slowly evolved over recent years. It’s also a book that marks a personal journey that touches on stories with a raw, heartfelt element as it winds its way through the Thames.

As part of the promotion for the book’s publication, Virginia embarked on a select number of personal appearances and readings. At Rough Trade East in London, she also took part in a Q&A session with poet and writer Will Burns. This provided an opportunity for Virginia to talk a little about the influences for the book and possible plans for the future.

“This collection came about as a result of attempting to write a prose book about the Thames – and particularly about the lock keepers and the people who worked on the river” commented Virginia at the start of the event. “As I had grown up on the Thames, I wanted to go back and see if they were still there in their lock houses.”

This was back in 2011 and it marked a dark period for the lock keeping community. Under threat from an environment agency who had plans to make one lock keeper cover lots of locks, while also renting out the idyllic cottages for premium rents.

“The first lock keeper I spoke to was a man called John at Buscot Lock, which is the second lock down on the Thames. There’s forty-five locks on the river and the river flows from the source up near… well, the middle of nowhere really in Gloucestershire.”

This location, known as Thames Head, influenced the book’s first poem, ‘Source’, which Virginia read for the first part of the event.

As with the book, Virginia’s readings took the audience on a journey down the river. “So, we go a little bit further from the source and go through places like Cricklade where the river starts to become navigable for small rowing boats and kayaks. And a little further in, at Lechlade, the river is now fully navigable and at one time this was a major centre for barges.”

“This next poem is called ‘Brandy Island’, and it features a man called Robert Tertius Campbell, who came back from Australia having made his money in gold with very, very big plans. He decided that he wanted to have the most highly industrialised farm in the country. As one of his major features, he was going to grow sugar beet and to distil it to spirit alcohol to sell to the French as brandy.”

For the reading of her poem ‘Buscot’, Virginia returns to the conversations she had with the lock keeper there, touching on the poem’s line about voices from the weir. “And that’s true that John does always hears voices in his weir and I think all lock keepers are very attached to their weirs. They always say ‘my weir’. And the weirs are very different too. Each weir has different operatives and it is a dark art. It’s something that people just learn over years and the information and experiences passed on by word of mouth.”

Speaking to the lock keepers allowed aspects of this life to be unveiled, but Virginia had realised something quite crucial: “I started to think ’Well, all my information is second hand’. It’s not really my own experience, apart from the fact that I grew up on the river.” As a result, Virginia searched online and saw that there was a job advertised for a lock keeper’s assistant. Taking on the role back in 2011 allowed her to get a much closer look at river work (and in fact she continued with the job for the next two years) which in turn influenced more of her writing.

“In 2012, I was a lock keepers assistant based at Benson and 2012, you may not remember, was the wettest summer. It was so unbelievably wet. And the water was so high that lots and lots of boats didn’t really travel on the river at all. They were not allowed to travel, it wasn’t safe.”

This experience was a little daunting for Virginia at the time. “I could hardly cross over the weir, let alone think about working there. It was terrifying.” But this experience led to the creation of the poem ‘The Weir at Benson’ with its energetic lines about “the white noise flanged” and “from upriver the water bore/gorging down, almost solid.”

The experiences also awoke things within Virginia that she had forgotten. “So many things I thought I’d left behind in memories kind of resurfaced. And quite a lot of them were quite sad.” These ideas are borne out through the “remembered landscape” detailed in the poem ‘I Breathe As Though I’ve Been Submerged And Am Coming Up For Air’.

The tradition of swan upping is one of the river’s oldest activities. Originally designed to apportion ownership among the Crown, the Vintners and the Dyers, the activity is now more focussed on checking the health of the swans. “But because of the rain and the high river, they couldn’t do it that year“ mused Virginia, “It was the first time it was cancelled in five hundred years.”

But in 2013, Virginia returned for the swan upping session (which takes place between Sunbury-on-Thames to Abingdon-on-Thames). Her experiences resulted in the colourful narrative of her piece ‘Swan-upper’.

Virginia returned to her roots for her next reading, an evocative ‘Moulsford To Cleeve’. “This poem relates to an incident many, many years ago when I did my album, From Gardens Where We Feel Secure. This poem is pretty much about me remembering… remembering.” The incident in question was later immortalised in the track ‘When The Fields Were On Fire’, a haunting composition that appears to play with the idea of memory with gauzy indistinct segments and sombre piano melodies.

The readings event was followed by a special Q&A where Virginia was quizzed on the genesis of The English River by poet Will Burns. Will was named as one of the 4 Faber & Faber New Poets for 2014 and is Poet-In-Residence at Caught By The River.

Will Burns: Maybe it would be a good place to start if we talked about how your musical past – or your sense of music – has fed into writing poems or prose. Are they linked in anyway or are they separate?

Virginia Astley: No, I think they are very linked. I think they are kind of hybrid versions of the same things – songs and poems. It certainly feels that I’m using the same bit of me if I’m writing a song or a piece of music or a poem.

There are references in the poems like the first three lines of The Weir At Benson (“The white noise flanged and phased, filtered as the wind…”), do they come out completely naturally or is it something you feel…?

Well, I always think of the weir as being like white noise and then I’m thinking that yes, the effect of the wind or the effect of the white noise or the effects of while you’re walking – or the voices carrying over the river – all of these things sound like they could be in the studio or sitting at home or whatever, just altering a basic sound in some kind of way.

Does the idea of a poem exist as a sound for you before it has a meaning?

I think for me it’s always the feeling that comes first but I’m always taking notes. So even if it’s just a phone or using my phone to take photos, I’m always sort of recording things that I’m thinking “Oh, I can use that or I like that”. So, I’m always storing stuff. And then how it actually ends up coming out is not necessarily the same time or in the way I imagined.

Let’s talk about the photos in the book.

I was primarily taking the photos as a way of remembering the river when I wasn’t there so that I was able to write my prose book about the river. And then I had lots and lots of photos. Then a couple of years ago I thought “Oh, I’m going to try taking out all the prose and all the photos and put them in together”, just selected photos, from my big mass of photos.

It seemed to work. And that’s how the book came about. In a way it was a kind of default thing. The only thing is that it’s all landscape, but it’s so familiar to me and I even hadn’t registered until recently that how it’s the same territory of From Gardens Where We Feel Secure, that particular album. So, it’s as though I’m like a person who only has one song (laughs). It’s the same area, it’s all the same stuff.

Outside the poems, how exactly did the river figure in your life? How did it fit in with other aspects of your life?

Well, I think I’ve very often lived by the river. Like I was saying, my first record company being at Wapping, at Metropolitan wharf and literally the doors opened onto the river. And I was living in Pimlico by the river. I lived in Twickenham, near the river. I grew up in Oxfordshire, near the river. So, it was a reoccurring theme without me kind of realising it. But there’s something about returning to the river and the sense of standing by the river and what that does to many of us. Particularly a place that we feel attached to. I can’t really explain it, but it was something that I realised was always there even though I hadn’t actually fully registered it until I started writing.

They are quite English poems, specific to a place. I wonder what they meant to you?

Well, it’s a funny thing too because when I was young, in reviews and things, people would always say and go on about the Englishness of my music and I used to hate that. But I don’t mind now. Oh well (laughs).

This book has a particular aspect of the personal. There’s this element throughout of somebody you are addressing, love affairs that seem to be in the peripheral view of the speaker of the poems.

I think that’s the way I write really. I think I write to work things out. I walk to work things out and I write to work things out. So, in a way I’m not really thinking necessarily of the end product. And I was the same writing songs. I think actually many of my songs are deeply, deeply personal but I never felt that I was exposing myself because I always thought I’d put masses of echo on and no one would be able to make out the words (laughs). You can’t really do that with poems, it’s all really clear in print. It’s my way of working things out a lot of the time. Sometimes I worry that there’s too much about me.

In a way, what is the landscape without the human in the landscape ?

Also, we all resonate with each other don’t we? You know, a common experience? You write something and it touches somebody else, or their experience as well.

Following the interview with Will Burns, questions were invited from the floor to discuss The English River, future books, influences and potential new music projects…

What did you use to take the photographs in the book?

Just my iPhone, like an early iPhone. Some I did with my camera which isn’t a very particularly flash camera but most were with my iPhone. And I wasn’t really trying to take great photos, I was more – as I was saying before – literally trying to record the landscape and remembering it.

I recall that during an interview you mentioned that when you were traveling down the river it reminded you of From Gardens. I just wonder whether you might have taken some recordings as well?

That’s exactly what I was doing, and I did do some recordings. And I do intend to do that, to go back to that. And I didn’t get anything that was particularly great, but I still have got ideas for the same territory… at night or something. You know, whatever (laughs)…underwater I think – the glops of carp!

Is Thomas Hardy an influence on your poetry?

I think Hardy probably is an influence. I was there last night, at Max Gate, ‘til quite late. There is such a wealth of poetry there. There’s nothing really conscious where I go, “Oh, I’m going to do that”. But I think just by being there, and the amount I’ve read by being there, and being the writer-in-residence at Hardy’s Cottage in the autumn too and walking all the time in that landscape, I’m sure it has some subliminal influence – or more than subliminal influence, yeah.

You were working on The Woodlanders many years ago as a musical project. Have you thought about revisiting that as a book?

As a book? No, I’m thinking more about revisiting it and getting some of the songs sung In Dorchester. There’s the New Hardy Players, who do Hardy productions each year. And I’m thinking about getting some kind of small version of The Woodlanders put on by some of them. Perhaps at Max Gate or Hardy’s Cottage… or out in the woods – better still! (laughs).

Are you still working on your other book, Keeping The River?

Yes, I am definitely. I’m really really hoping that having this poetry book out, I will find a publisher who would be interested in the whole book.

Thanks to Rough Trade East for staging the event and to Will Burns for hosting.

Q&A transcription by Rob Brown.